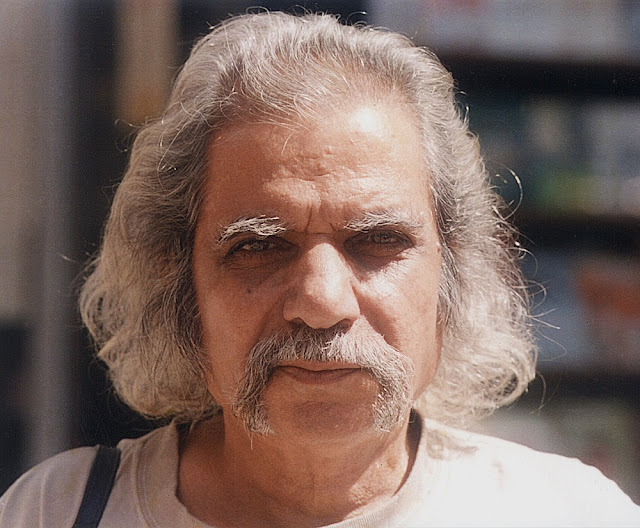

Arun Kolatkar

(1 Noviembre 1932 – 25 Septiembre 2004). Nació en Kolaphur, India.

Arun Kolatkar ha sido uno de los más importantes poetas modernos de la India. Sus textos, escritos en marathi y en inglés, descubren trazas de lo divino en un mundo en el que todo parecía perdido antes del poema.

Su primer libro de poemas en inglés, Jejuri, le conquistó el premio Commonwealth Writers’ Prize en 1977. Su obra, Bhijki Vahi, le hizo ganar el Premio de la Academia Literaria. Sus otros libros en inglés incluyen Sarpa Satra (2003) y Kala Ghoda Poems (2004). Trabajó como publicista y obtuvo varios premios como diseñador gráfico.

El sacerdote

Una ofrenda de talón y cadera

en el frío altar del muro de la alcantarilla

el sacerdote espera.

¿Acaso tarda un poco el ómnibus?

se pregunta el sacerdote.

¿Tendrá en su plato puran poli[i]?

Con un veloz encogimiento de testículos

al tacto de la toscamente cortada piedra, empapada de rocío

gira su rostro en el sol

para mirar al largo camino que serpea fuera de vista

con la irregularidad

de la línea de la fortuna en la mano de un muerto.

El sol agarra la cabeza del sacerdote

y da una palmadita en su mejilla

familiarmente como el barbero del pueblo.

El poco de nuez de betel

que se vuelve una y otra vez en su lengua

Esto funciona.

El ómnibus no es más que una idea en su mente.

Es ahora un punto en la distancia

Y bajo su holgazana vista de lagartija

comienza a crecer

con lentitud igual que una verruga en su nariz.

Con ruido sordo y una sacudida

el ómnibus cae en un bache y cruje al pasar al sacerdote

y pinta sus ojos de azul.

El ómnibus da vuelta en círculo.

Se para dentro de la estación y permanece

en suave ronroneo ante el sacerdote.

Una mueca felina en el frente

y un peregrino vivo, listo para comer,

agarrado entre sus dientes.

es como un mantra.

_________

Otro país.

Arundhathi Subramaniam, poeta, ensayista y compiladora

MANOHAR

La puerta estaba abierta.

Manohar pensó

que sería un templo más.

Miró adentro

preguntándose

qué dios iba a encontrar.

Se giró rápidamente

cuando un ternero de ojos grandes lo miró.

No es otro templo,

se dijo,

sino un establo simplemente.

_________________________

Traducción: Germain Droogenbroodt - Rafael Carcelén

de: “Twelve Modern Indian Poets”, Oxfort University Press

Promesas

Sacrificar una cabra delante del reloj

romper un coco en la vía del tren

manchar el indicador con la sangre de un gallo

bañar al jefe de estación en leche

y prometer que dará

un tren de juguete dorado a la encargada de reservas

si alguien le dijera

cuándo llegará el próximo tren.

___________

Traducción: Germain Droogenbroodt – Rafaél Carcelén

http://www.point-editions.com/new/es/promesas-abun-kolatkar-india/

Vows

Slaughter a goat before the clock

smash a coconut on the railway track

smear the indicator with the blood of a cock

bath the station master in milk

and promise you will give

a solid gold toy train to the booking clerk

if only someone would tell you

when the next train is due.

From: “Twelve Modern Indian Poets”

Oxford University Press

EL ESTE COMO PROFESIÓN

Por AMIT CHAUDHURI

Sobre el tema de la desfamiliarización, quizá sea útil analizar Jejuri, la famosa secuencia de poemas escrita por Arun Kolatkar y publicada en 1976.

De hecho, el extrañamiento se convierte, una vez más, en forma de distancia cultural, y las notas en un relato sobre la alienación; un relato, de hecho, de incertidumbre semiarticulada pero profunda sobre qué constituye, en el lenguaje, el asombro poético, la ciudadanía, la nacionalidad, y de qué modo estas categorías mantienen una tensión entre ellas. Abundan los ejemplos, pero daré sólo dos.

El primero se refiere a la nota que pone a «The Doorstep» [«El umbral»], un poema suficientemente breve como para citarlo en su totalidad:

Eso no es un umbral,

Es un pilar a su lado.

Sí.

Eso es lo que es.

That’s no doorstep.

It’s a pillar on its side.

Yes.

That’s what it is.

«Heart of Ruin» [«El corazón dela ruina»], el poema que precede a «The Doorstep» en la secuencia de Kolatkar. Como nos dice Raykar –y ésta es la información que da tanta utilidad a su libro y, puesto que carece de parangón, lo hace imprescindible–,el poema es «una descripción detallada del entonces descuidado templo deMaruti, en Karhe Pathar».

Desde los primeros versos, Kolatkar nos ofrece unretrato del estado de abandono del mismo, casual pero apasionado:

El tejado se cae sobre la cabeza de Maruti.

A nadie parece importarle.

Y mucho menos al propio Maruti.

Así cataloga Kolatkar la energía alborotada de la escena, al igual que el asombrado descubrimiento que hace de ella:

Una perra sin raza ha encontrado un lugar

para ella y sus cachorros

en el corazón de la ruina.

Quizá le guste más un templo así.

La perra te mira con cautela

Tras una entrada tapada por las tejas rotas.

Los cachorros parias se tambalean sobre ella.

Quizá les guste más un templo así.

El cachorro de la oreja negra se ha alejado demasiado.

Una teja suena bajo sus pies.

Basta para provocar el terror en el corazón

de un escarabajo pelotero

y hacerlo correr en busca de refugio

a la seguridad de la caja de recaudación rota

que no ha tenido oportunidad de salir

de debajo del peso aplastante de la viga del tejado.

Lentamente, el narrador concluye, y la frugalidad de Kolatkar con las comas le resulta útil en una frase en la que la segunda mitad no es ni una ampliación lógica ni una contradicción de la primera:

Al no ser ya un lugar de oración este lugar

es nada menos que la casa de dios.

Bestiario

José Morella

Arun Kolatkar, Collected poems in English, Bloodaxe Books, 2010.

Los dos poemas que presentamos pertenecen a Jejuri, su primer libro, publicado cuando Kolatkar tenía ya 44 años.

Los dos poemas que presentamos pertenecen a Jejuri, su primer libro, publicado cuando Kolatkar tenía ya 44 años.

El corazón de la ruina

El techo le cae a Maruti en la cabeza.

A nadie parece importarle.

A Maruti, a quien menos.

Quizá prefiera que los templos sean así.

Una perra callejera y sus cachorros

han encontrado sitio

en el corazón de la ruina.

Quizá prefiera que los templos sean así.

La perra, alerta, te mira cruzar

un umbral de escombros de azulejos rotos.

Los cachorros parias le corretean por encima.

Quizá prefieran que los templos sean así.

El de las orejas negras se aventura un poco.

Pisa un azulejo y hace un ruido.

Eso basta para infundir terror en el corazón

de un escarabajo

y hacer que corra a cobijarse

al amparo de la caja rota de las limosnas

que no tuvo ocasión de escapar

de debajo del peso aplastante de una viga.

Ya no es un lugar de culto este lugar

sino nada menos que la casa de dios.

Heart of Ruin

The roof comes down on Maruti's head.

Nobody seems to mind.

Least of all Maruti himself.

May be he likes a temple better this way.

A mongrel bitch has found a place

for herself and her puppies

in the heart of the ruin.

May be she likes a temple better this way.

The bitch looks at you guardedly

past a doorway cluttered with broken tiles.

The pariah puppies tumble over her.

May be they like a temple better this way.

The black eared puppy has gone a little too far.

A tile clicks under its foot.

It's enough to strike terror in the heart

of a dung beetle

and send him running for cover

to the safety of the broken collection box

that never did get a chance to get out

from under the crushing weight of the roof beam

No more a place of worship this place

is nothing less than the house of god.

Una vieja

Una vieja se te prende

de la manga

y te sigue adonde vayas.

Quiere una moneda de media rupia.

Dice que te va a llevar

al santuario de la herradura.

Tú ya has estado ahí.

Igualmente cojea junto a ti

y te agarra la camisa aún más fuerte.

No te va soltar.

Sabes cómo son las viejas.

Se te pegan como sombras.

Te giras y la encaras

con un gesto como de zanjar.

Quieres acabar con la farsa.

Cuando la oyes decir

«¿qué otra cosa va a hacer una vieja

en estas colinas miserables?

Miras directo al cielo.

Atravesándole los boquetes de bala

que tiene por ojos.

Y conforme la miras

las grietas que empiezan en torno a sus ojos

se expanden más allá de su piel.

Y las colinas se agrietan.

Y los templos se agrietan.

Y el cielo se viene abajo

con un estrépito de vajilla

alrededor de la bruja irrompible

que es lo único que queda en pie.

Y tú eres reducido

a tanta calderilla

en su mano.

An Old Woman

An old woman grabs

hold of your sleeve

and tags along.

She wants a fifty paise coin.

She says she will take you

to the horseshoe shrine.

You've seen it already.

She hobbles along anyway

and tightens her grip on your shirt.

She won't let you go.

You know how old women are.

They stick to you like a burr.

You turn around and face her

with an air of finality.

You want to end the farce.

When you hear her say,

"What else can an old woman do

on hills as wretched as these?"

You look right at the sky.

Clear through the bullet holes

she has for her eyes.

And as you look on

the cracks grietas that begin around her eyes

spread beyond her skin.

And the hills crack.

And the temples crack.

And the sky falls

with a plateglasss clatter estrépito

around the shatter proof crone

who stands alone.

And you are reduced

to so much small change

in her hand.

© 2013 Luke

The Bus

The tarpaulin flaps are buttoned down

on the windows of the state transport bus.

all the way up to jejuri.

a cold wind keeps whipping

and slapping a corner of tarpaulin at your elbow.

you look down to the roaring road.

you search for the signs of daybreak in what little light spills out of bus.

your own divided face in the pair of glasses

on an oldman`s nose

is all the countryside you get to see.

you seem to move continually forward.

toward a destination

just beyond the castemark beyond his eyebrows.

outside, the sun has risen quitely

it aims through an eyelet in the tarpaulin.

and shoots at the oldman`s glasses.

a sawed off sunbeam comes to rest gently against the driver`s right temple.

the bus seems to change direction.

at the end of bumpy ride with your own face on the either side

when you get off the bus.

you dont step inside the old man`s head.

Scratch

What is god

and what is stone

the dividing line

if it exists

is very thin

at jejuri

and every other stone

is god or his cousin

there is no crop

other than god

and god is harvested here

around the year

and round the clock

out of the bad earth

and the hard rock

that giant hunk of rock

the size of a bedroom

is khandoba's wife turned to stone

the crack that runs right across

is the scar from his broadsword

he struck her down with

once in a fit of rage

scratch a rock

and a legend springs

The Reservoir

There isn't a dropp of water

in the great reservoir the peshwas built.

There is nothing in it.

Except the hundred years of silt.

Traffic Lights

Fifty phantom motorcyclists

all in black

crash-helmeted outriders

faceless behind tinted visors

come thundering from one end of the road

and go roaring down the other

shattering the petrified silence of the night

like a delirium of rock-drills

preceded by a wailing cherry-top

and followed by a faceless president

in a deathly white Mercedes

coming from the airport and going downtown

raising a storm of protest in its wake

from angry scraps of paper and dry leaves

but unobserved by traffic lights

that seem to have eyes only for each other

and who like ill-starred lovers

fated never to meet

but condemned to live forever and ever

in each other's sight

continue to send signals to each other

throughout the night

and burn with the cold passion of rubies

separated by an empty street.

The Hoeshoe Shrine

That nick in the rock

is really a kick in the side of the hill.

It's where a hoof

struck

like a thunderbolt

when Khandoba

with the bride sidesaddle behind him on the blue

horse

jumped across the valley

and the three

went on from there like one

spark

fleeing from flint.

To a home that waited

on the other side of the hill like a hay

stack.

.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario